What is Arthritis?

Arthritis is a long-term condition affecting joints, which can have a substantial impact on quality of life. It is an umbrella term used to describe Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid arthritis, and Gout arthritis.

Osteoarthritis

A type of arthritis that occurs when flexible tissue at the ends of bones wears down. The wearing down of the protective tissue at the ends of bones (cartilage) occurs gradually and worsens over time. Joint pain in the hands, neck, lower back, knees or hips is the most common symptom.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease that can cause joint pain and damage throughout your body. The joint damage that Rheumatoid arthritis causes usually happens on both sides of the body. So, if a joint is affected in one of your arms or legs, the same joint in the other arm or leg will probably be affected, too. This is one way that doctors distinguish Rheumatoid arthritis from other forms of arthritis, such as osteoarthritis.

Gout arthritis

Gout arthritis is a build-up of uric acid in the blood, which can then form crystals in the joints. As gout arthritis relates to the build-up of excess uric acid, risk factors for increased urate concentrations are considered to increase the risk of developing gout arthritis.

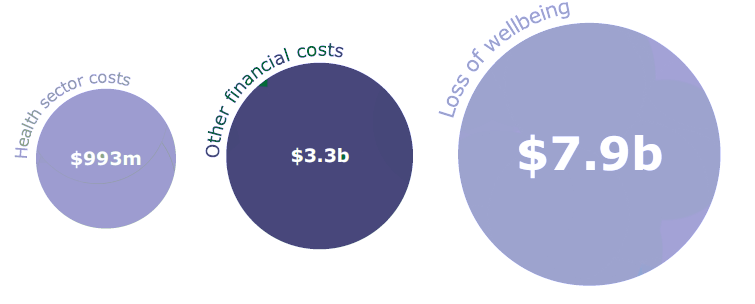

Costs associated with arthritis

The total cost of arthritis in New Zealand is estimated to be $12.2 billion in 2018. The costs of arthritis comprise both financial costs, which include health sector costs, productivity losses and the cost of caring for people with arthritis, as well as loss of wellbeing for people with arthritis.

Prevalence of arthritis in New Zealand

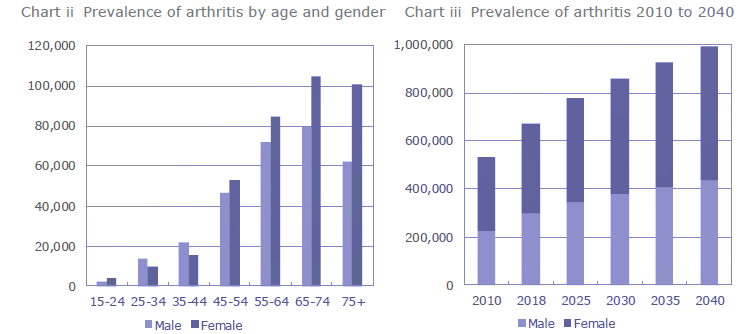

In 2018, approximately 670,000 New Zealanders aged 15 or over are living with at least one type of arthritis. This equates to 17.0% of the population aged 15 or over, or 1 in 6 people.

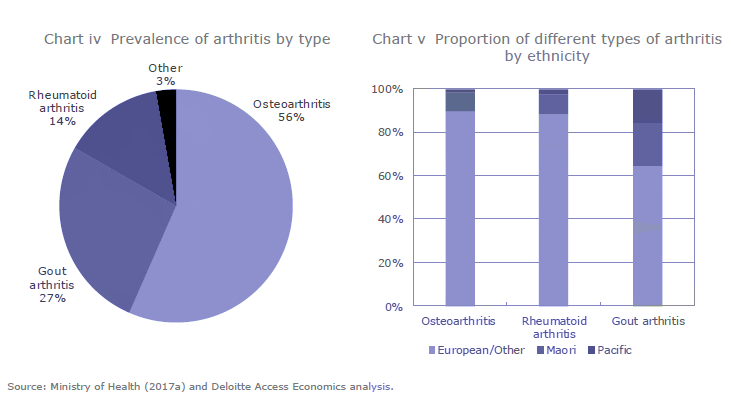

Osteoarthritis is the most prevalent form of arthritis in New Zealand, followed by gout arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Treatment and prevention

Primary treatment with non-pharmacological components involve people maintaining a healthy lifestyle, with emphasis on exercising and healthy eating.

- nutritional changes

- lose weight (if overweight) to help protect joints from being overworked

- participate in physical therapy to keep joints mobile

- undergo surgery, which may be required to repair or replace damaged joints

Risk factors for arthritis

A number of genetic and environmental factors have been found to be associated with the development of arthritis. Known risk factors associated with all forms of arthritis include:

- Modifiable risk factors such as excessive weight, manual and repetitive tasks, physical injuries, smoking and dietary.

- Non-modifiable factors such as age, gender and genetics.

In general, the more risk factors a person has, and the greater severity of each risk factor, the greater the likelihood of developing arthritis. The following sub-sections individually discuss the presence of risk factors in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and gout arthritis.

Osteoarthritis

There are a range of factors associated with at-risk population for osteoarthritis. Age, obesity and physically demanding activities or occupations were identified as relevant risk factors in the development of osteoarthritis in knees, hips and hands.

Age is the strongest risk factor in the progression of osteoarthritis. While osteoarthritis may begin at any age, it usually affects people over 40 years of age. This may be a result of cartilage changes with ageing, where the water content of the cartilage decreases, causing cartilage to be less resilient.

“Although the degeneration of joints associated with ageing can contribute to osteoarthritis, recent research suggests that the condition is not an inevitable consequence of growing old and may even be preventable. “

Obesity is one of the most modifiable risk factors for osteoarthritis. Obesity refers to the accumulation of excessive fat in the body, defined in terms of Body Mass Index (BMI). Studies have found that the risk of developing hip and knee osteoarthritis increases by 11% and 35%, respectively when there is a 5-unit increase in BMI. The mechanism by which obesity increases the risk of developing osteoarthritis can be both mechanical and inflammatory. For example, the extra weight in obese patients can place heavier loads on their joints making them susceptible to joint injury. On the other hand, the correlation between obesity and hand osteoarthritis suggests that inflammatory factors are also at work.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in metres squared (kg/m²). Adults with BMI of 30.0 or greater (or equivalent) are identified as being obese.

In genetics, a locus is the place a gene occupies on a chromosome.

In addition, injuries (particularly for knee osteoarthritis) and physically demanding activities can also contribute to the development of osteoarthritis. In particular, the risk of developing the condition were found to be higher in occupations associated with heavy physical work load, constant kneeling, squatting or standing, and repetitive movements.

“For instance, farmers are found to have a higher risk for osteoarthritis.”

A number of studies have also found evidence of genetic influence in the development of osteoarthritis. Genetic factors were found to account for at least 50% of the cases of hand and hip osteoarthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis

The development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis encompass a range of genetic and environmental factors. The hereditary nature of rheumatoid arthritis is evident in literature, with genetic contribution to susceptibility estimated to be around 65% using Finnish data. Genome-wide association studies have characterised more than a hundred loci associated with rheumatoid arthritis risk. Okada et al have, for instance, identified 98 biological candidate genes at 101 risk loci.

Environmental factors can also place people at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis, with smoking, infection, dietary factors, environmental pollutants and urbanisation thought to make a person prone to developing the condition. For example, early research found women who smoked at least 25 cigarettes a day for more than 20 years had a 39% increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis relative to non-smoking women. Hormonal factors are also considered to increase the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis, with women found to be three times more likely to have this condition than men, and oestrogen is known to have an effect on the immune system.

Gout arthritis

Increasing age, male gender and ethnic origin are found to be associated with gout arthritis. In New Zealand, compared to Europeans, gout arthritis was found to be more prevalent in Māori (particularly in Māori men) and a stronger family history of gout arthritis in Māori was identified. The association between certain ethnic groups and susceptibility to gout arthritis development suggests the importance of genetic predisposition.

As with other forms of arthritis, environmental factors also play a role in the progression of gout arthritis. Established dietary risk factors associated with gout arthritis include excessive consumption of alcohol and red meat. Recent research also found consumption of sugary beverages contributes to increase risk of gout arthritis. Medications are additionally associated with the risk of gout arthritis. Some medicines such as diuretics (tablets that drain water from the body) used to treat high blood pressure can cause gout arthritis. In addition, chronic diseases, such as kidney diseases, diabetes and obesity, were found to be associated with the risk of gout arthritis.

Take home messages

- Arthritis is a highly prevalent condition that affects around 17% of people in New Zealand aged over 15 years.

- Arthritis prevalence increases with age, for people aged over 65 years more than 45% of people have some form of arthritis.

- It is estimated that 1 million New Zealanders will have arthritis by 2040.

- Arthritis has a large cost to the New Zealand economy.

References

- Abajobir et al. (2017). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet, 390(10100), 1211-1259.

- Access Economics. (2005). The economic cost of arthritis in New Zealand. Report for Arthritis New Zealand, Canberra.

- Access Economics. (2007). Painful realities: the economic impact of arthritis in Australia in 2007. Report for Arthritis Australia, Canberra.

Access Economics. (2010). The economic cost of arthritis in New Zealand. Report for Arthritis New Zealand, Canberra. - Anderson, A. S., & Loeser, R. F. (2010). Why is Osteoarthritis an Age-Related Disease? Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology, 24(1), 15.

- Annemans, L., Spaepen, Gaskin, Bonnemaire, Malier, Gilbert, & Nuki. (2007). Gout arthritis in the UK and Germany: Prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 67(7), 960-6.

- Arthritis Australia. (2014). Time to Move: Arthritis [Brochure]. Australia: Arthritis Australia. Retrieved from: https://arthritisaustralia.com.au/wordpress/wpcontent/uploads/2017/09/Final_Time_to_Move_Arthritis.pdf

- Arthritis New Zealand. (2014). Rheumatoid Arthritis [Brochure]. Wellington, New Zealand: Arthritis New Zealand.

- Arthritis New Zealand. (2017). 2017 Annual Report. Retrieved from: https://www.arthritis.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-proof-OB-15969-Arthritis-Annual-Report-proof-V2-new.pdf

- Arthritis New Zealand. (2018a). Form of Arthritis. Retrieved from: https://www.arthritis.org.nz/information/forms-of-arthritis/

- Arthritis New Zealand. (2018b). Out with Gout arthritis [Brochure]. Wellington, New Zealand: Arthritis New Zealand.

- Arthritis New Zealand. (2018c). National plan needed for osteoarthritis care. Retrieved from: https://www.arthritis.org.nz/national-plan-needed-for-osteoarthritis-care/

- Arthritis & Osteoporosis Tasmania. (2016). Counting the cost: the Current and Future Burden of Arthritis. Tasmania, Australia: Arthritis Australia.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015). 4430.0.30.002 – Microdata: Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2015. Retrieved from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/PrimaryMainFeatures/4430.0.30.002? OpenDocument (Access by subscription)

- Baldwin, J., Briggs, A., Bagg, W., & Larmer, P. (2017, December 17). An osteoarthritis model of care should be a national priority for New Zealand. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 130(1467), 78-86.

- Banderas, B., Skup, M., Shields, A., Mazar, I., & Ganguli, A. (2017). Development of the Rheumatoid Arthritis Symptom Questionnaire (RASQ): A patient reported outcome scale for measuring symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 33(9), 1643-1651. Commercial-in-confidence The economic cost of arthritis in New Zealand in 2018.

- Batt, C., Phipps-Green, A.J., Black, M.A., Cadzow, M., Merriman, M.E., Topless, R., … Merriman, Tony R. (2014). Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: A risk factor for prevalent gout arthritis with SLC2A9 genotype-specific effects on serum urate and risk of gout arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 73(12), 2101-2106.

- Beukelman, T., Patkar, N., Saag, K., Tolleson-Rinehart, S., Cron, R., Dewitt, E., … Ruperto, N. (2011). 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care & Research, 63(4), 465-82.

- Briggs, A.M., Woolf, A.D., Dreinhofer, K., Homb, N., Hoy, D.G., Kopansky-Giles, D., Akesson, K., & March, L. (2018). Reducing the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions. World Health Organisation. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.204891

- Brouwer, W., Van Exel, N., Van de Berg, B., Dinant, H., Koopmanschap, M., & Van den Bos, G. (2004). Burden of caregiving: Evidence of objective burden, subjective burden, and quality of life impacts on informal caregivers of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research, 51(4), 570-577.

- Burton, W.N., Chen, C.Y., Schultz, A.B., Conti, D.J., Pransky, G., & Edington, D.W. (2006). Worker Productivity loss associated with arthritis. Disease Management, 9(3), 131-43.

- Care and Support Workers (Pay Equity) Settlement Act 2017 (New Zealand). Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2017/0024/28.0/DLM7269150.html

- Choi, J.W.J., Ford, E.S., Gao, X., Choi, H.K. (2008). Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum, 59(1),109–116.

- Cicuttini, F.M, & Wluka, A.E. (2014). Osteoarthritis: Is OA a mechanical or systemic disease? Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 10(9), 515-6.

- Croft, P., Cooper, C., Wickham, C., & Coggon, D. (1992). Osteoarthritis of the hip and occupational activity. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 18(1), 59-63.

- Dalbeth, N., Merriman, T.R., & Stamp., L.K. (2016). Gout arthritis. The Lancet, 388(10055), 2039-2052.

- Dunkin, A.M. (2015, April). More than just joints: How Rheumatoid Arthritis Affects the Rest of Your Body. Retrieved from https://www.arthritis.org/about-arthritis/types/rheumatoid-arthritis/articles/rhemuatoid-arthritis-affects-body.php

- Giles, L. C. (2007).Do social networks affect the use of residential aged care among older Australians? BMC Geriatrics, 7(24). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-7-24

- Grotle, Margreth, Hagen, Kare B., Natvig, Bard, Dahl, Fredrik A., & Kvien, Tore K. (2008). Obesity and osteoarthritis in knee, hip and/or hand: An epidemiological study in the general population with 10 years follow-up. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 9(132), 132.

- Guillemin, F., Saraux, Guggenbuhl, Roux, Fardellone, Le Bihan, … Coste. (2005). Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in France: 2001. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 64(10), 1427-1430.

- Hak, A., Curhan, G., Grodstein, F., & Choi, H. (2010). Menopause, postmenopausal hormone use and risk of incident gout arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 69(7), 1305-9.

- Harrison, A. (2013). How to treat. New Zealand Doctor, 35-40. Commercial-in-confidence The economic cost of arthritis in New Zealand in 2018

- Harrold, L., Salman, C., Shoor, S., Curtis, J., Asgari, M., Gelfand, J., … Herrinton, L. (2013). Incidence and prevalence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis among children in a managed care population, 1996-2009. The Journal of Rheumatology, 40(7), 1218-25.

- Health Navigator Editorial Team. (2018, May 14). Health Navigator New Zealand. Retrieved from Rheumatoid arthritis: https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/health-a-z/r/rheumatoid-arthritis/

- Health Navigator Editorial Team. (2018). Retrieved from Health Navigator New Zealand: https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/health-a-z/g/gout arthritis/

- Health Navigator Editorial Team. (2018). Retrieved from Osteoarthritis: https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/health-a-z/o/osteoarthritis/

- Helmick, C., Felson, D., Lawrence, R., Gabriel, S., Hirsch, R., Kwoh, C., … Stone, J. (2008). Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part I. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 58(1), 15-25.

- Hooper, G., Lee, A., & Rothwell, A. (2014). Current trends and projections in the utilisation rates of hip and knee replacement in New Zealand from 2001 to 2026. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 127(1401), 82.

- Hunter, D., York, M., Chaisson, C., Woods, R., Niu, J., & Zhang, Y. (2006). Recent diuretic use and the risk of recurrent gout arthritis attacks: The online case-crossover gout arthritis study. The Journal of Rheumatology, 33(7), 1341-5.

- Inland Revenue. (2016). GST (Good and Services Tax). Retrieved from http://www.ird.govt.nz/gst/.

- Jacobi, C., Van den Berg, B., Boshuizen, H., Rupp, I., Dinant, H., & Van den Bos, G. (2003). Dimension-specific burden of caregiving among partners of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology, 42(10), 1226-1233.

- Jiang, L., Rong, J., Wang, Y., Hu, F., Bao, C., Li, X., & Zhao, Y. (2011). The relationship between body mass index and hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine, 78(2), 150-155.

- Karlson, E., Lee, I., Cook, N., Manson, J., Buring, J., & Hennekens, C. (1999). A retrospective cohort study of cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in female health professionals. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 42(5), 910-917.

- Klemp, P., Stansfield, S., Castle, B., & Robertson, M. (1997). Gout arthritis is on the increase in New Zealand. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 56(1), 22-26.

- Kuo, C., See, L., Yu, K., Chou, I., Chiou, M., & Luo, S. (2013). Significance of serum uric acid levels on the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Rheumatology, 52(1), 127-134.

- Li, X.A., Gignac, M.H., & Anis, A. (2006). The Indirect Costs of Arthritis Resulting from Unemployment, Reduced Performance, and Occupational Changes While at Work. Medical Care, 44(4), 304-310.

- MacGregor, A., Snieder, H., Rigby, A., Koskenvuo, M., Kaprio, J., Aho, K., & Silman, A. (2000). Characterizing the quantitative genetic contribution to rheumatoid arthritis using data from twins. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 43(1), 30-37.

- Manners, P., & Bower, C. (2002). Worldwide prevalence of juvenile arthritis why does it vary so much? The Journal of Rheumatology, 29(7), 1520-30.

- Manners, P., & Diepeveen, D. (1996). Prevalence of juvenile chronic arthritis in a population of 12-year-old children in urban Australia. Pediatrics, 98(1), 84-90. Commercial-in-confidence The economic cost of arthritis in New Zealand in 2018

- Ministry of Health. (2010). Health Expenditure Trends in New Zealand: 2000-2010. Retrieved from https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/health-expenditure-trends-in-new-zealand-2000-2010.pdf

- Ministry of Health. (2013) Health Loss in New Zealand: A report from the New Zealand Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study 2006-2016. Wellington, New Zealand.

- Ministry of Health. (2017a). Annual Update of Key Results 2016-17 New Zealand Health Survey. Retrieved from https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2016-17-annual-data-explorer/_w_627fa094/#!/home

- Ministry of Health. (2017b). Equipment and modifications for disabled people. Retrieved from https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/services-and-support/disability-services/types-disability-support/equipment-and-modifications-disabled-people

- Ministry of Health. (2018a). Regional Results of 2014-17 New Zealand Health Survey. Retrieved from https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/regional-results-2014-2017-new-zealand-health-survey

- Ministry of Health. (2018b). Arthritis. Retrieved from: https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/conditions-and-treatments/diseases-and-illnesses/arthritis

- Ministry of Health. (2018c). The case for the MAP. Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Social Development (2017). Annual Report 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/corporate/ annual-report/2017/annual-report-2017.pdf;

- Ministry of Social Development. (2018a). Supported Living Payment. Retrieved from: https://www.workandincome.govt.nz/products/a-z-benefits/supported-living-payment.html#null

- Ministry of Social Development. (2018b). Supported Living Payment – March 2018 quarter. Retrieved from: https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/statistics/benefit/latest-quarterly-results/supported-living-payment.html#Annualcomparison2

- Ministry of Social Development. (2018c). New Zealand Superannuation (NZ Super). Retrieved from: https://www.workandincome.govt.nz/eligibility/seniors/superannuation/index.html

- Ministry of Transport. (2017). Social cost of road crashes and injuries 2017 update. Wellington, New Zealand.

- New Zealand Health Quality and Safety Commission. (2016). Atlas of Health Care Variation: Gout arthritis 2012-14. Retrieved from https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/Health-Quality-Evaluation/Atlas/gout arthritisSF14Jan/atlas.html

- New Zealand Orthopaedic Association. (2017). Retrieved from New Zealand Joint Registry 17 Year Report: Jan 1999 to Dec 2015: https://nzoa.org.nz/nz-joint-registry

- New Zealand Treasury. (2016). Discount Rates. Retrieved from https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/state-sector-leadership/guidance/financial-reporting-policies-and-guidance/discount-rates

- OECD. (2017). Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/health-at-a-glance-19991312.htm

- Office for Disability Issues and Statistics New Zealand. (2009). Disability and Informal Care in New Zealand in 2006. Wellington, New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand.

- Okada, Y., Wu, D., Trynka, G., Raj, T., Terao, C., Ikari, K., … Plenge, R. M. (2014). Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature, 506(7488), 376–381. Commercial-in-confidence The economic cost of arthritis in New Zealand in 2018.